In a parallel universe, a popular thinker like Thomas Frank correctly identified the problem currently tearing the US and much of the world apart. In this alternate reality, this thinker may have even been able to proffer a solution, given a keen enough intellect or the right insight.

Instead, in our

reality Thomas Frank (like many turn-of-the-21st-century American

liberal public intellectuals) noted a strange phenomenon in conservative

states. If you’ll pardon an eye-rolling pun, he saw that blue collar folks were

reliably voting red. That is to say: poor and working people were voting

against their economic self-interest by electing politicians who promised to

(and then proceeded to) dismantle the very safety nets and regulations that

most benefited their voters. Frank’s treatment of this issue, the widely-read

and well-regarded What’s

the Matter with Kansas?, was published in 2004.

Frank’s answer to his book’s titular question is,

essentially, “culture wars.” Kansas maintains that conservative

politicians appeal to voters’ base and easily-manipulated prejudices through

issues like abortion, gun control, etc. A more advanced and thoughtful version

of this basic thesis can be found in the Marxist concept of false

consciousness, the idea that capitalist institutional power generates an

ideological fog that blinds the proletariat to the dire economic circumstances

of their day-to-day life. Television, “common sense,” the political

dog-and-pony show: all exist to distract and confuse the working class and

provide ersatz contentment. In one

passage, Marx referred to religious ideology in particular as flowers placed upon and

concealing the chains that bind us to our place in an exploitative system.

|

| Karl Marx |

Marx wrote in a very specific and interesting theoretical milieu: 19th-century Germany. This was before the first rise of fascism, though proto-fascist philosophical strains had already started to wrap themselves around European thought. When Friedrich Nietzsche put pen to paper, he gave shrill voice to a strange form of reactionary thinking born as the shadow cast by the Enlightenment. The father of conservative thought, Edmund Burke, made his own contribution. Burke wrote Reflections on the Revolution in France back in 1790. His rejection of liberté, égalité, fraternité was couched in language about the slow, organic nature of society and the superiority of gradual change guided by elites to the idea of revolution. He buttressed his opposition to the French Revolution by advancing a theory of the individual as subordinate to the institutions vital to human identity. Churches and the like were “little platoons,” valuable because they metaphorically whipped us into shape, providing us with our sense of “I.” Burke’s reaction to the political advances of the Enlightenment were conservative, however, and mild compared to the contempt poured on modernity by Nietzsche and other proto-fascist German thinkers.

To Nietzsche, “God is dead” wasn’t a celebration, but a shrill

wail of lamentation. Nietzsche wasn’t anti-religion in the least, despite what

his disciples among college freshmen might think. He wanted that old

time religion, preferably something akin to the era

of Moses or the religious caste system in India. He was a violent

reactionary, raging against the rising tide of equality, democracy,

rationalism, and individuality. Another example of this coagulating German thoughtform

can be found in historian and philosopher Oswald Spengler’s 1918 whopper The

Decline of the West. Spengler, like Nietzsche, despised both modernity

and liberalism. Spengler thought “the West” was in the dread state of

“civilization,” which he defined (oddly) as the terminal stage of a culture.

“The West” and modernity were both on their way out, Spengler believed, as a

function of repeating cycles that followed a pattern (this “history as a

predictable process” framework was also central to the ideas of Hegel and Marx,

not coincidentally).

|

| Helena Blavatsky |

Other bizarre currents were present in the Germany of this era as well; strange strains of esotericism and what we would now call new religious movements (or “cults,” to be crude). Helena Blavatsky, for example, stole, bastardized, counterfeited, and exploited sources ranging from traditional Western Esotericism to “Eastern thought.” After she commenced her schtick, our poor planet had Theosophy to contend with. A few spores from this new family of religions and philosophies thrived with particular vigor in Germany, including so-called Ariosophy. My point in sketching this thumbnail of the pre-fascist pseudo-philosophical milieu of that time and place – one that appears engaged (at least in our century) in what Nietzsche would call “the eternal return” – is to provide context for the following statement:

Of the three major political theories that went to war in

the mid-20th-century – communism, liberalism*, and fascism –

liberalism is by far the weakest when it comes to understanding the true nature

of what drives humanity. Liberalism views human desire as more powerful

than other drives, and as more or less benign and materialistic to boot. To

capitalist democracies like the United States, the mainstream political bargain

goes something like this: support our institutions and in exchange we offer you

comfort, safety, freedom to do what you like, and stability. A chicken in every

pot, a college education for those who can either afford it or go into debt for

it, a mortgage for every hardworking family unit, and contented evenings of time

in the company of one’s choosing. Whether capitalism actually provides these

things is relevant to a broader discussion of all three ideologies, but not for

this piece, in which we are only looking at the specific question of what

motivates political decisions that seem irrational.

(* - Liberalism in the political theory sense, not the American electoral

sense. In theory, liberalism refers to a combination of democratic or

republican governance, a more or less regulated market system, individual

rights and liberties, a legalistic approach to citizenship, etc.)

“Who on Earth wouldn’t want that?” Thomas Frank, in

essence, asks. “What has hypnotized and bewitched these people? Why aren’t they

acting rationally to fulfill their material needs and desires?”

|

| Breadline by George Luks, 1900 |

The answer to “who” is easy: quite a few people, actually. Why? For reasons that are complicated, sad, and a little mysterious. Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs (first articulated in a 1943 paper and then fleshed out in 1954’s Motivation and Personality) is not a biological law. It is not a scientific theory that has been experimentally tested, nor is it particularly philosophically rigorous. It is, to boil it down, a theoretical outline for psychology and, most often, a tool used in management training. In the 70-odd years since Dr. Maslow conceived of this hierarchy, quite a few assumptions in psychology have quite rightly been challenged and, in many cases, toppled. Maslow’s hierarchy has unfortunately not been overthrown (yet), and remains a major conceptual framework used to teach generations of therapists, managers, sociologists, and other representatives of the administrative/bureaucratic class.

To Thomas Frank’s eyes, the entranced voters of Kansas are

behaving counter to Maslow’s hierarchy, and their behavior can be explained by

crafty Republican exploitation of the so-called American “culture war.” What

they should be focused on is their own rational self-interest. This certainly

lines up with the liberal conception of the human animal. What is best for

citizens materially has been at the center of ideological sub-types ranging from

early thinkers like John Locke and John Stuart Mill right up to small-d

democratic small-l liberal modernity (including everyone from libertarians to

centrists like Barack Obama and Joe Biden). Liberal governance is a peaceable

affair (if it isn’t and includes election tampering or even, as in the case of

Russia, assassination

of critics and opponents, it is by definition not liberal governance). It

promises rational debate, pluralism, material comfort, social progress, and

stability. Again, whether it actually provides those things is up for debate.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Julius

Evola (an Italian fascist philosopher), and even drunken, half-bright slobs

like Steve

Bannon understand something about the human animal that the great thinkers

of liberal modernity do not. They understand that many citizens of liberal

democracies feel in some way

unfulfilled. The Marxian critic in me would chalk this up to the widening

gap between classes, the decline of labor unions, and the atomization of

sociality inherent to capitalism and consumer culture. What created the hole,

so to speak, doesn’t matter as much as how a society fills it.

|

| The Scream, Edvard Munch 1893 |

Discrete right-wing movements like Evangelical Christianity approach this problem with a combination of the mystical-political (universal salvation, the Kingdom of God and the Second Coming / Apocalypse, etc.) and the practical. The practical comfort that Evangelical culture produces is twofold, and serves as a perfect example of the double-edged blade of social capital (in a nutshell: the collective bonds and sociability demonstrated by participation in civic and community-building activities including service clubs, collective recreational activity like bowling leagues, etc.). On the one hand, Evangelical churches provide a very real and hugely beneficial community for the in-group. “Community” is more than an abstract: it represents a group of humans who care about one’s well-being in a non-transactional way. On the other hand, the dark side of in-group social capital is even more in evidence in Evangelical congregations than its benefits. This is also the case with organizations like the Ku Klux Klan, the German-American Bund, and other violent, nightmarish groups. The dual nature of such groups was on display in, for example, Klan gatherings at which they shared a family picnic meal at the site of a lynching – an incomprehensibly obscene juxtaposition of both the vilest and the most normal of human behaviors. The in-group’s contempt for the out-group was so pronounced that “very fine people” felt comfortable dining while enjoying the spectacle of murder.

In other words, the ability to form an “us” in liberal democracy seems to rely on (or at least be most reliably expressed through) fear, anger, and hatred*. In the absence of class-based solidarity, and with the emptiness of much that has been commodified, commercialized, or privatized, little else is left. One can root for a sports team, especially a local one – and there is some intriguing research being done that indicates that sports fandom produces an especially fierce and unpredictable form of social capital (it does, however, also have the violent downsides mentioned above). Alternately, if one is seeking connection to an “us” in the liberal democracy, one can assume a stake in a political party, a form of participation that, frankly, has a lot in common with sports fandom. These identities provide a goal to strive for, a group to strongly identify with, and (perhaps most importantly) a common enemy at whom one can direct the liberating and intoxicating emotions of anger and hatred.

(* - Rebecca Solnit makes a convincing case in A Paradise Builtin Hell that strong, social-capital-based communities also develop in the wake of disasters or crises such as Hurricane Katrina or the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. However, this follows the thesis of this essay, as such bonding is triggered by disruptive, deadly, and catastrophic conditions.)

If those components sound familiar, and if the chanting,

flag-waving, and violence at sports events remind you of Nuremburg circa 1939 a little bit, I’d

argue that you’re on the right track. That isn’t to say that sports fandom is

inherently fascistic; only that sports fandom satisfies the same essential

human drives that fascism parasitizes. Fandom engages the same props essential

to the metaphorical “play” that mass events like these almost always rely on: flags, symbols,

uniforms,

colors with special

significance, and – through jeering, booing, and the like – even a real-life version of the “two minute hate” that George Orwell so

chillingly wrote about in 1984.

So – with all this in mind, let’s examine Thomas Frank’s question again. What’s the matter with Kansas? Why do they vote against their economic self-interest?

First: because the promises of material improvement and “the

good life” have, for the most part, failed to materialize in any substantial

way in broad swaths of the liberal democratic world. Second: because in the

absence of such prosperity, liberal democracy gives citizens very little

to take social or political sustenance from. Currently and in the United States,

this vacuum of meaning has largely been filled by Evangelical Christianity,

which has failed to improve people’s material circumstances but has provided an

element of community lacking in the decaying civil life of the US – but modern,

politically-engaged Evangelical Christianity has

evil, poisonous roots in racist authoritarianism, and predictably it has

trended more and more toward a sort of theocratic

quasi-fascism. For the purposes of this essay, modern Evangelical

Christianity in the US may thus be thought of as a sub-type of America’s

current fascist upswell. Third (and perhaps most importantly), “the hole in one’s soul” and the

feeling of unfulfillment which seem to accompany capitalistic / materialistic

liberal democracies has found resolution. Much off America (from Washington

state all the way to

Florida) have passed through what Max Weber called Entzauberung

(“disenchantment”) and have found the results wanting. In their desperation,

many have turned to the hyper-reactionary philosophy called “the Dark Enlightenment.”

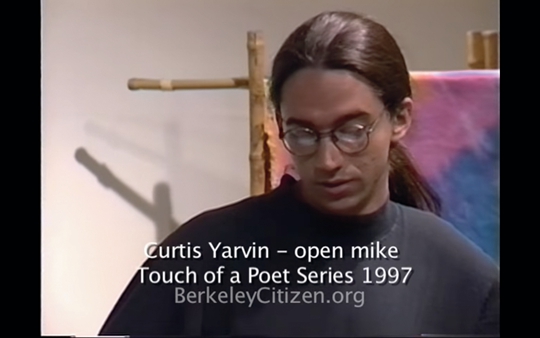

|

| "Mencius Moldbug," the king without a kingdom |

“The Dark Enlightenment” is a 21st century movement of counter-rationalism, anti-individualism, anti-democratic anti-egalitarianism, and a rejection of the scientific worldview. It was first articulated by Mencius Moldbug (real name Curtis Yavin) and his disciple Nick Land. If these names and concepts sound cartoonish, irrational, or perhaps even absurd, that is intentional. Such antics are part of the defense mechanisms of this loose coalition of ideologies. They prefer, for the most part, to be dismissed by “serious thinkers” or – better yet – to remain anonymous and distribute their work where it will find purchase. Inevitably, Moldbug’s spores grew best in the fertile and feces-fertilized soil of online alienation and internet nihilism. The fruit of Moldbug’s labors isn’t a monocultural crop: his writing has born fruits ranging from a resurgence of Catholic Monarchism to völkisch Ásatrú, a racist revival of Norse and Germanic heathenry that is making inroads in small-town America. To anyone with a passing acquaintance with the history of bloody and protracted death-struggles between the Roman Catholic Church and heathenry in old Norse and Germanic regions, the revival of the two ideologies from a common root source is puzzling, if not incomprehensible*.

(* - The specific rabbit hole of neo-reactionary religious

syncretism and the 21st-century magick revival is one I’ll be

writing about quite a bit in the near future, so if that subject interests you

stay tuned.)

The lodestone of this bumper crop of neo-reactionary

movements is telling, because it is the foundation stone of fascism. What these

superficially diverse anti-Enlightenment ideologies share is a deep,

foundational commitment to Kampf

und Streit: struggle and strife. They are, in essence, fascist at their

core, whether they dress the concept up in Indian mysticism, Norse

revivalism, Evangelical

Christianity (by way of British Israelism),

or materialistic and atheistic National Socialism. The appeal of violent

struggle in the name of a fundamentalist ideology, whether that ideology is revolutionary Communism

or revolutionary Fascism,

should not be underestimated. However, where revolutionary Communism, revolutionary

democratization, and even revolutionary political Islam have end states

(which Eric Hoffman’s The

True Believer referred to as the “end of the active phase” of a mass

movement), fascism has no such end state. In part, this stems from fascism’s

conception of time – an essay or book in and of itself – but it’s also part of

fascism’s sneaky tactical brilliance. Fascism’s natural state is strife,

struggle, war, and death. Any proffered “golden age” (such as the ever-imminent,

never-realized Tausendjähriges

Reich) is window dressing at best and certainly not key to its appeal.

|

| Consummattum Est, Matthias Grünewald 1512-1516(?) |

The appeal of Kampf und Streit to Christians is obvious: Christianity is a religion founded on the strife, struggle, suffering, and death of its titular messiah. In an incalculable number of Catholic churches and cathedrals, for example, artistic portrayals of the agonizing death of Jesus are prominently displayed. Through sculpture, stained glass, or paint, Catholics are reminded on a weekly basis that their salvation and eternal life were bought with terrible pain and struggle. Christianity’s fixation on the torture and death of Jesus of Nazareth produces a flock of the faithful who are, from childhood, taught the virtues of violent death and struggle against a fallen and corrupt world that is out to get them.

My point here is not to cast Christianity as a fascist

doctrine: that would be foolish, discriminatory, and factually impossible to

reconcile. What I am saying, however, is that Christianity uses the same

potent cocktail of fear, aggression, longing, and disenchantment to bind its

followers together that fascism – and many other reactionary ideologies – also

use. Fascism is the most potent of these neo-reactionary ideologies, having

been custom-built in the 20th century to hijack the alienation of

post-Enlightenment humanity. One of the earliest and most effective tactics it

deployed was to cast postwar life in the Germany of the 1920s and 30s as impoverished.

They meant not so much the absence of prosperity (although the Nazi Party did

speak to that a little) as the absence of the real keys to an authentic

life: struggle, suffering, and death in the name of something greater than

one’s self. Naziism provided a pre-built worldview that met these strange

desires. They provided enemies (Jews, communists, etc.), a mighty and united

effort (to expand Germany’s borders through aggressive military action), a

place in that very same united effort (either military service, Party

membership, or involvement in any of the startling

abundance of Nazi civic and Party clubs, training regimes, etc.), and –

perhaps most importantly - Kampf und Streit.

|

| Sisyphus, Titian 1549 |

In conclusion, then, let’s reexamine our imaginary question from Thomas Frank regarding the reactionary nature of many working-class people in the United States.

“Who on Earth wouldn’t want prosperity?” In theory, nobody –

but proponents of Enlightenment values, capitalism, and liberal democracy have

vastly overestimated the appeal of mere prosperity.

“What do people want if they don’t want prosperity, freedom,

and individual self-actualization?”

Death, Mr. Frank. Struggle, strife, and death in the name of

a grand, epochal cause. It’s not logical, it’s not pretty, and it’s not likely

to make one optimistic, but as a proud product of the Enlightenment and a

proponent of its virtues, I am committed to the truth as I can best know it –

and the truth is that there’s nothing wrong with Kansas. At least, nothing that

hasn’t been wrong with humanity for at least the last century, and in all

likelihood millennia longer than that.

Fortunately for the future of humanity, death isn’t the only (or even primary) impulse that drives social and political behavior. If it were, we would have self-immolated long ago. The primal need that underlies the Sturm und Drang of late-19th to early-20th century German proto-fascism, the need that hides behind flags, slogans, violence, and struggle, is the need for meaning. In his typically acerbic and off-kilter manner, Eric Hoffman derided this as “the true believer’s need to be relieved of the terrible burden of self.” Nietzsche was terrified by modernity’s lack of “horizons” (limits, definitions, established roles, etc.) because of the terrible freedom such a lack represented. Said freedom is only terrifying if one has no meaning; no metaphorical flame to cast light and lead one through the darkness of one’s frail and insignificant life. There are countless meanings to give one’s life to and, at the moment, liberal democracy seems to be losing its appeal. One possible solution (or, at least, strategy) is for liberal theorists and politicians to eschew the patronizing and moralistic practice of condemning perfectly natural and vitally important human drives.

The left (in American political terms) has, of late, modeled

itself after the moral code of the Jedi Order, to use a particularly geeky

metaphor. Anger, hate, fear – all “negative emotions” are backgrounded in order

to foreground the “superior emotions” of love, solidarity, etc. Those who

advocate this approach should take note of how easily and often the Jedi were

dismantled by the Sith, who (unlike their goody two shoes counterparts)

embraced their passions, including anger. Learning to expand one’s moral palate

doesn’t mean descending into aggressive lunacy. Quite the opposite: tempered,

controlled anger can sustain a pacifistic protest longer than “love.” Hatred of

war or racism or other social ills is a much more motivating impulse than is

usually acknowledged by the left – and that’s too bad. Movements like the mid-20th-Century

Civil Rights Movement, Black Lives Matter, opposition to the Vietnam War, etc.

were animated by a full spectrum of emotional needs and expressions, not just

the safe, polite ones pre-selected by the political or theoretical elite. Those emotions we consider "negative" are, by and large, rooted in passion - that which also drives love, loyalty, and the like.

|

| Worker's Holiday - Coney Island, Ralph Fasanella 1965 |

Not only that, these leftist movements provide strife and struggle, but provide them in a constructive, progressive, largely-peaceful way. What’s more, where right-wing and/or fascist ideologies stoke passions against minority communities who are largely powerless and oppressed, leftist rage is most often directed at those who wield an outsized influence over the lives of working people due to their wealth and/or institutional prominence. To put it another way, right-wing anger punches down while left-wing anger punches up.

Anger, struggle, strife: these are concepts that make

bourgeoise liberals uncomfortable. Some of whom remember the 1960s through the

distorted and largely-useless lens of nostalgia and the light of sanitized historical

narrative rather than that of true history. We forget the “nasty” parts of

political progress at our peril. The most dangerous, poisonous, destructive,

and anti-human ideology that our world has thus far produced remembers these

lessons. To combat the rising tide of the Fascist Internationale, liberal

democracies need to do some soul-searching about what they do and do not offer

their citizens. Such conversations are taking place already, whether the left

wants to participate or not.

Comments

Post a Comment