Metaphors! You know them, you love them, you need them – but much like motor vehicles, semiautomatic rifles, and pet chinchillas, they are easily abused!

While some form of half-assed licensing is required for

cars, guns, and exotic pets, the idea of licensing metaphors or tagging them

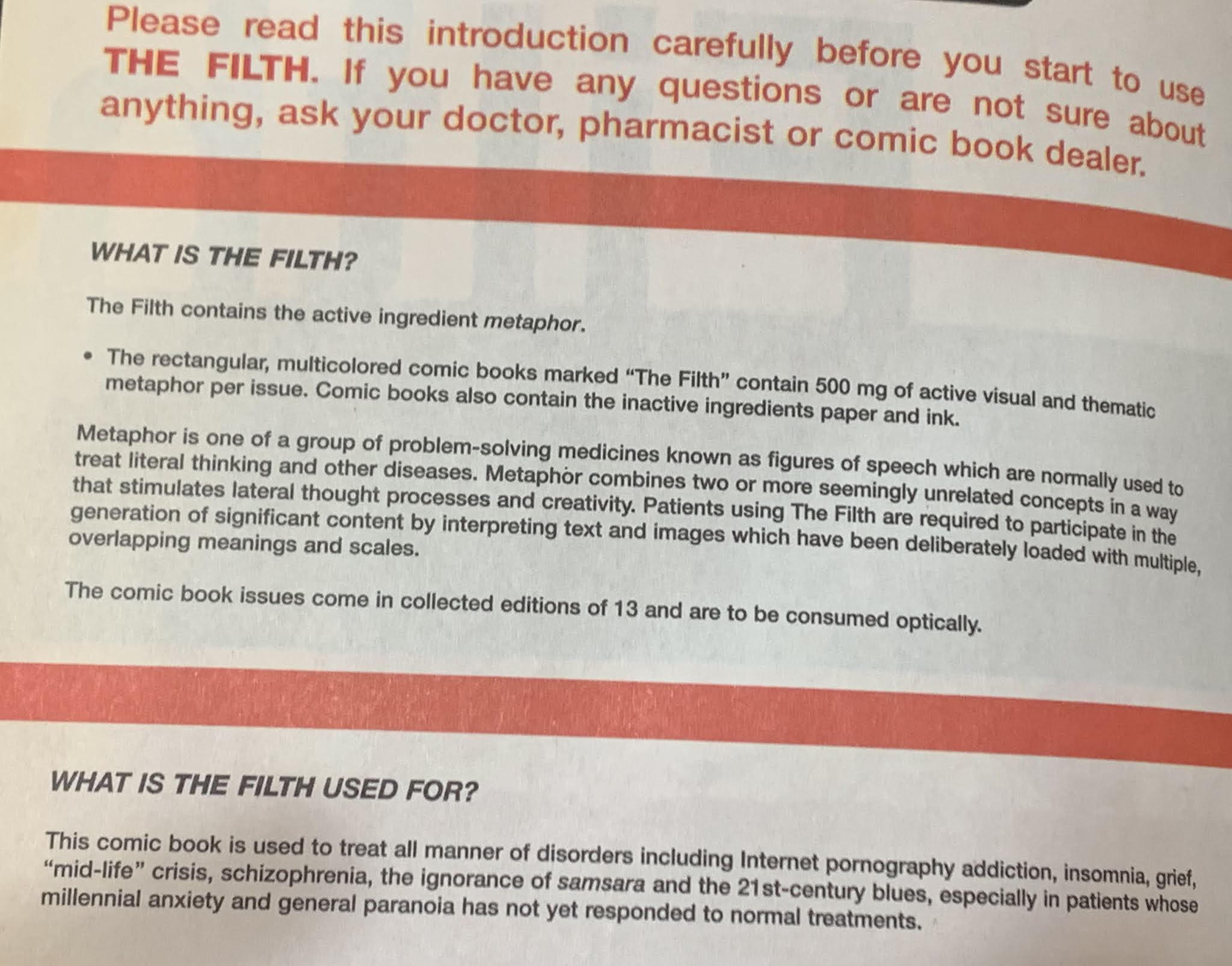

with some kind of warning is absurd. Right, Grant Morrison’s The Filth?

Don’t tell that to human

lobster and alt right professor of semiotics clinical psychologist Jordan

Peterson! In fairness, he’s dumbest when he talks about culture or

politics: his book Maps

of Meaning just seems like another contribution to the niche carved by

books like George Lakoff’s excellent Metaphors

We Live By. My favorite exploration of this theme was penned by Jorge

Luis Borges. His On

Exactitude in Science, originally published in 1946, is staggeringly

brilliant. It’s a one-paragraph short story in the form of a literary forgery,

and explores the so-called map-territory

relation (a term coined by Alfred Korzybski in a 1931 paper called “A

Non-Aristotelian System and Its Necessity for Rigor in Mathematics and Physics”

– obviously the inspiration for Borges’ piece, given that Exactitude’s

original Spanish title translates

better as “Rigor” than “Exactitude”).

We need metaphors because the world is incomprehensible. It’s

far too vast and interrelated across time and space for a puny human mind (or

even the best supercomputer we can build) to comprehend as a unified, singular

system. Unified systems, however, are how humans attempt to manage the world

and our relationship to it and each other. Thus, metaphors simplify and render

legible processes which otherwise would remain mysterious. Our species’

earliest attempts to think about reality were expressed in metaphors that took

the form of gods,

spirits, and legends. Unfortunately, our pre-scientific efforts made

reality “comprehensible,” in a sense, but failed to give us control over it or

a way to interact with it (since gods, spirits, and legends aren’t real and do

not explain material reality or physical processes in a useful way).

Did god-metaphors and mystical thoughtforms “set us back,” in terms of technological progress? It’s impossible to know. It’s difficult to disregard them completely: such thoughtforms were extremely useful in maintaining social control and cohesion. Even so, some god-metaphors took on a destructive and terrifying life of their own (such as the Jesus Christ of the Crusades, for example). In other words, we need metaphors to understand the world - as long as those metaphors are 1) useful in comprehending material reality or social processes, and/or 2) beneficial rather than destructive.

Bad metaphors breed an inaccurate or fanciful understanding

of reality, both our material existence and the relationships and dynamics between

humans and the world. I have a white-hot, burning hatred of the widespread and

widely-believed metaphor at the

heart of dualism (a metaphor I would express as “world-as-separate” or “world-as-death”),

but that’s an extended discussion for another day. Today, we pick the

low-hanging fruit of mangled metaphors that lead to mangled thinking.

By “mangled” I mean a trite metaphor or idiom mis-expressed

as its exact opposite or inversion – i.e., “what goes down must come up”

instead of “what goes up must come down.” The former is based on life inside the

Earth’s velvety gravity; the latter is, I don’t know, maybe true for Aquaman?

The mangled metaphor I hate most has become commonplace on the political right, especially as a dimwitted encapsulation of the issue of police malfeasance. In cases ranging from corruption to outright murder, you will often hear the following: “Don’t let a few bad apples spoil the whole bunch,” or (as shorthand for that version of the expression) “a few bad apples.” The original saying is actually “A few bad apples spoil the whole bunch” – literally the opposite of the thin-blue-line, I-love-the-cops, asshole version.

This misunderstanding of an old saying is telling. In the original (and agriculturally accurate) expression, the “apples” were people engaged in a given activity. The warning that a “few bad apples” would ruin the entire barrel was based on material reality, in which corruption spreads from fruit to fruit until – by association – all of the fruit becomes corrupt. The idea of the expression is that, like apples, humans can pick up negative ethical habits from each other*. The message is that people must be vigilant and stamp out bad behavior before it spreads to others, because such corruption is inevitable.

In the mangled version, the apples are still people and the

rot is still corruption – but we are told to disregard (rather than seek out

and reject) the “bad apples,” because, hey, just a few corrupt people doesn’t really

say anything about a department, organization, or other group, right? It’s an

inversion of reality intended to dismiss or explain away corruption as a series

of isolated incidents, when in all likelihood corruption

is a systemic problem.

Two examples of this metaphor in action spring immediately to mind. One of them is, in fact, police corruption: the “bad apples” idiom is an incorrect (and totally wrongheaded) understanding of both problem and solution. When “bad apples” appear in a police department, the cops’ answer is often to swiftly and quietly transfer them rather than take their badge and gun. The correct understanding of “bad apples” would lead departments to reject bad cops outright with the knowledge that laxity in self-regulation inevitably leads to the spread of ethical rot.

Another example is the way in which the Catholic Church has dealt

with pedophile priests since at least the 20th Century (when records

of such things began to be kept – I suspect it has been a problem for, oh, two

millennia before that?). The correct understanding of “bad apples” would have

led the church to immediately fire and file charges against such men. The

mangled understanding excuses the church’s actual reaction which was to shuffle

said priests from location to location as quickly and quietly as possible. As a

result, countless thousands of children were abused by oft-excused,

oft-transferred “bad apples,” because, hey – doesn’t spoil the whole bunch,

right?

Metaphors matter – as do the specific words we use, the

affect we adopt when kicking ideas around, and many other phenomena that are

not directly related to language so much as they underpin it. In

this occasional series, I’ll continue to explore mangled metaphors and great metaphors

alike – if you’re a semiotics nerd like me, I hope you will enjoy it!

Comments

Post a Comment